Periyar’s imprint on Tamil Nadu politics

EV Ramasamy (Periyar) was largely drawn towards public life from his early years. He served the people of Erode with great dedication during the spread of plague in the early years of the 20th century and even carried dead bodies abandoned by relatives for dignified burial. He did wander across the country dressed as a Hindu monk to places like Varanasi (Kasi), Kolkata (Calcutta), Asansol, Puri, Ellore and Bejawada to gain knowledge and firsthand account of the Hinduism and its practices including the role of superstitions, behaviour and the conduct of Hindu priests in these religious places. Periyar’s decision to leave the Congress in 1925 on the ground that the party was not committed to abolishing caste discrimination and untouchability was one of the crucial turning points in the history of social justice movement in the Madras Presidency and subsequently towards defining the course of politics in Tamil Nadu.

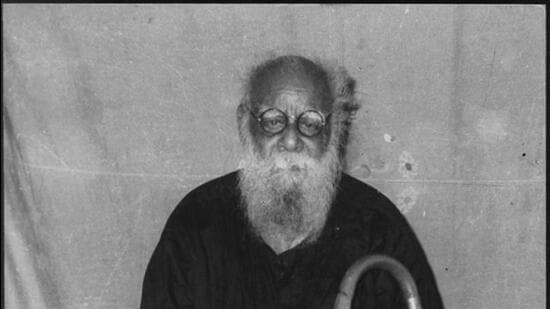

Periyar joined the Congress in 1919 because he was deeply drawn by the ideals of Gandhi and the quest for freedom (HT)

Periyar joined the Congress in 1919 because he was deeply drawn by the ideals of Gandhi and the quest for freedom. Periyar was a dedicated member of the Congress and campaigned for khadi with great energy and enthusiasm. He carried khadi clothes on his shoulders to encourage and spread awareness about the national movement for freedom from the British colonial rule and the significance of khadi among men and women in the Madras Presidency. Periyar, known as the father of the Dravidian movement, was not originally a member of the Justice Party that was established on 20 November 1916. The founding members of the Justice Party were C Natesa Mudaliar, TM Nair, PTheagaraya Chetty and Alamelu Mangai Thayarammal. The foundation of Justice Party, officially the South Indian Liberal Federation, was the culmination of historical efforts in the late 19th and early 20th century to seek representation for the non-Brahmins in the administration and politics of the Madras Presidency.

After assuming the charge of the president of the Congress for the Madras presidency, Periyar advocated reservation for the non-Brahmins in education and employment in government. He wanted the Congress to take keen interest in the subject of reservation(s) for the non-Brahmins but he was distraught by the indifference and lukewarm response of the Congress. He continued to press for resolution to this effect in Trichy (1919), Thirunelveli (1920), Thanjavur (1921), Tiruppur (1922), Salem (1923) and Thiruvannamalai (1924). He was dismayed by the lack of response and believed that Congress party was controlled by the dominant caste and class considerations. Periyar’s Vaikkom struggle (1924) was an indication of his courage and determination to fight against the practices of untouchability and discrimination of marginalised people and communities even beyond the boundaries of Madras Presidency. Though Periyar and Rajaji were great friends for a long time yet Periyar found his moves and initiatives were shrewdly blocked by Rajaji on a number of occasions. Periyar’s appeal and subsequent meetings with Gandhi also did not bear fruits.

The Kanjipuram Conference of the Congress Party (1925) became a final breaking point between Periyar and the Congress when he pressed for the resolution advocating the reservations for the non-Brahmins and the tabling of the resolution was denied on the ground that it would affect the common good. This was the end of his association with the Congress and Periyar vowed never to return to the Congress and resist the Congress for rest of his life. The end of his association with the Congress marked the beginning of a new era in the politics of Madras Presidency and giant leap to the social justice movement in Tamil Nadu. Periyar launched the self-respect movement in 1925.

Periyar welcomed the caste based reservation approved by the Dr Subbarayan-led ministry supported by the Justice Party in 1928. The first state level conference of self-respect movement was held in February 1929 in Chengalpet was both an historical and significant for several reasons including 34 radical resolutions that were passed at this conference. It needs to be observed that Justice Party was faced with a criticism of its leaders being elites from the non-Brahmin communities and the peaking of the nationalist struggle for freedom in the early 1930s also contributed to the electoral setbacks for the party. Congress under the leadership of Rajaji won the January 1937 elections and Justice party was humbled and its leaders were dejected by the developments. Periyar encouraged the leaders of the Justice Party to preserve their energy and vision as well as wait for their time to come. The decision to make Hindi compulsory subject in the schools by the Rajaji led Congress government in 1937 reinforced a new vigour and dynamism into the politics of the state that would survive even beyond hundred years. The language politics acquired a critical dimension in the national debate on identity and power. Periyar sought self rule for the Tamil territory by the Tamils and did not believe that the rights and interests of the Tamils could be protected under the political and constitutional framework of India.

Another remarkable development took place with the election of Periyar as the president of the Justice Party in December 1938 while he was serving prison imprisonment in Chennai. Periyar continued to resist against the imposition of Hindi and succeeded in the withdrawal of Hindi as the compulsory subject at the school through a governor’s order in February 1940. The opponents of the Congress at the national level such as Mohammed Ali Jinnah and MN Roy began to take notice of Periyar and to add surprise to the turn of events in politics, even Rajaji defended Periyar’s call for a separate nation depending on the ground that people genuinely desire and support such a demand. Rajaji at this stage had already resigned from the Congress by 1942 after supporting the partition of India into India and Pakistan. In August 1944 another significant move was undertaken by Periyar at the Salem conference of the Justice party. The self-respect movement and the Justice party were integrated with a view to establish broad based peoples’ movement in the name of “Dravida Kazhagam”, and thus preserving the continuity and changes within the social justice movement in Tamil Nadu. This was another defining moment in the history of Dravidian movement in the south and in the state of Tamil Nadu.

Periyar held strong reservations about the electoral politics right from the beginning. Periyar’s aversion or indifference to electoral politics would later continue to be major point of contention between him and his political disciple CN Annadurai (Anna). Though it is attributed that the marriage of Periyar with Maniyammai, who was 41 years younger than himself, was the major reason for the final split between Periyar and Anna implying the change of guard and custodian of the Dravida Kazhagam (DK) yet the truth remains that Periyar sensed the urge and anxiety of Anna and his followers to enter electoral politics and contest the elections. The result was the birth of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) on September 17, 1949 at the Robinson Park in Chennai. The rest is history with the tear drops of Periyar turning into ocean of support in less than two decades of time with DMK rising to power in March 1967 in Tamil Nadu.

(Prof Ramu Manivannan is a Fulbright Scholar – Political Scientist – Social Activist in areas of education, human rights and sustainable development. He is currently the Director, Multiversity – Centre for Indigenous Knowledge Systems, Kurumbapalayam Village, Vellore District, Tamil Nadu)

Images are for reference only.Images and contents gathered automatic from google or 3rd party sources.All rights on the images and contents are with their legal original owners.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.